MYTH vs. FACT: Iranians & Western Culture

/By Sarah Witmer, Research Associate

MYTH: Iranians are isolated from the world and have limited access to Western products and culture. What they know about the West they don’t like, as evidenced by their chants of “Death to America.”

FACT: Despite years of sanctions from abroad and a government that censors much of the media and internet, Iranians actually have broad understanding of and access to Western culture and products. Daily life for young Iranians - particularly those in the major cities - would look quite familiar to most Westerners.

An Introduction to the Iranian People

When Americans picture Iran, they tend to recall the events of 1979: the Islamic Revolution that overthrew a westernized monarch in favor of an Islamic Republic, or the storming of the American Embassy and the ensuing hostage crisis. Many Americans picture Iranians marching through city squares in Tehran, burning American flags and effigies of American presidents. As former president Ahmadinejad once mockingly noted, there is a stereotype amongst Americans that Iranians spend their waking moments “sitting in the desert, turned toward Mecca and waiting to die.”

In reality, of course, images of Iranians as hostile, radical zealots are grossly inaccurate stereotypes of an educated and culturally receptive people where over sixty percent of college graduates are female. A photograph from the project Humans of Tehran captures two female students sitting in the grass with sketchbooks and iPhones, describing Salvadore Dali as “wonderfully weird.” Close to 35,000 Iranians come to the U.S. each year; many as students.

Shirin Barghi, an Iranian journalist now based in New York, began Humans of Tehran to dispel myths about modern-day Iranians so “demonized and divorced from reality.” In Humans of Tehran photo albums, young girls ride skateboards with iPod earbuds poking out of their mandatory hijab. A shopkeeper at Tommy Hilfiger stands behind a Christmas tree, peering out the window at the photographer. Muslim clerics sitting on a park bench smile for the camera. In these photographs, the subjects embody a combination of global modernity and Iranian tradition. Similar scenes are found in cities throughout Iran; a travel log by an Iranian journalist for Vice describes teenagers riding mountain bikes across centuries-old town squares in Isfahan, and vendors at bazaars in Shiraz and Tehran selling mountains of spices next to counterfeit Gucci bags. As the travel journalist describes, Iran is “a country where vastly different understandings of the world live side by side.”

These vastly different understandings, however, can lead to conflict: Iranians must carefully tread the line between “Western” and “Islamic” practices, at risk of severe punishment for failing to do so to the satisfaction of the government. Barghi describes the challenge of convincing people to pose for her Humans of Tehran photographs; in the past, the government has published photos of protesters in newsletters as a means of political intimidation and blackmail. Undercover “morality police” officers patrol public spaces throughout Iran for signs of “un-Islamic” conduct: particularly women not wearing a proper hijab, dressing in a manner that is considered too revealing, or wearing makeup that is deemed excessive.

Despite the difficulties, modern technology like cellphones and illegal Twitter and Facebook accounts, often serve as tools for resistance to government control. One example is the project My Stealthy Freedom, started by Masih Alenijad, an Iranian journalist living in exile in the U.S., where women post photographs of themselves in public defiantly holding their hijabs in their hands. Through the project, Alenijad notes that many Iranian men have been unexpectedly supportive, contrary to arguments by the morality police and conservative religious leaders that women without hijab are tempting men to attack and take advantage of them. “Men in Iran are educated and cultured,” Alenijad states. “They are reacting positively because they support women having the freedom to choose... The younger generation of men are very supportive, but also the older generation have daughters and children and they want them to have the freedom of choice.”

Introduction to Iranian Life

US politicians tend to lump Iran with North Korea when describing it as isolated from the world, underdeveloped and even a “failed state,” as White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer recently labeled Iran. However, American citizens and policymakers holding this view might be surprised to discover that daily life in Iran is replete with the same technology, brands, and interests that are common in the West.

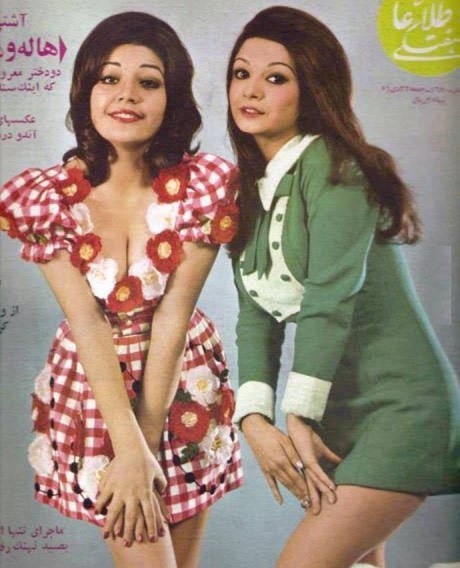

After so many years of hostility between the US and Iran, it is understandable that many may not recall a time when the US and Iran were strong allies and when life in Iran was nearly synonymous with US culture. Many young Westerners today, who never knew this version of Iran are particularly surprised to see images of Iran from before the revolution that conflict with their expectations of the country. This Reddit discussion about the pre-1979 Iranian advertisement pictured here, and about Iranian culture in general, recently rose to the top of Reddit, reflecting the popularity of the topic and highlighting this lack of awareness.

As a result of the history between the two countries, many aspects of American culture are already quite familiar to Iranians. Even after the revolution, it is common for Iranians to travel back and forth visiting family since many families were split during the revolution (some stayed under the new regime and some fled -- mostly to the U.S). In fact between 0.5 million and 1 million people across the United States identify as Iranian-American, with the largest portion of this group--nearly 90,000 people--living in Los Angeles (one community in Beverly Hills is commonly referred to as “Tehrangeles,” where the streets are lined with signs in Persian). This informal exchange that takes place between communities in the U.S. and Iran contributes to familiarity with popular American entertainment and trends.

Partly as a result of these continued connections, Iranians enjoy Western products and brands. While sanctions and government restrictions have kept many Western businesses out of Iran since the revolution, Iran’s lax copyright laws allow for imitations and knockoffs. Instead of McDonald’s, Iran has its own, highly popular Mash Donalds. Instead of Pizza Hut, Pizza Hat. People sip frappuccinos from Café Raees (which, at least in branding, looks suspiciously similar to Starbucks), and order from KFC, or Kabooki Fried Chicken. Iranian state television channels have been known to broadcast Western films and television shows from illegal pirating sites; copyright laws protect Iranian work, but nothing else.

What matters more to Iranian government controllers, it seems, is whether films feature nudity than whether they are violating intellectual property laws. Other American brands, such as Pepsi and Coca-Cola, are allowed as they are, without the need for an Iranian re-branding to satisfy anti-Western conservatives. “It is also not a crime for an Iranian to chat on an iPhone, jog in a pair of Nikes or brush with Crest,” according to a column in the New York Times. It seems that the lifting of sanctions against Iran will in some ways simply legitimize existing Western influence, and in other ways provide competition from the real companies that Iranian entrepreneurs have copied; McDonald’s is already petitioning to re-open franchises that were closed in 1979.

Summary

While conservative Western and Iranian leaders alike suggest that their countries are diametrically, even morally opposed, regular citizens tell a different story. A 2016 poll found that the majority of Iranians (51%) hold a favorable view of the American people. The vast majority (68%) favor increased cultural, economic and educational exchanges, and over 80% of Iranians wished Americans and Iranians would visit each other’s countries as tourists more often. Indeed, Western tourists often find Iranians to be far more welcoming and kind than flag-burning images of them in the media suggest. Recently, Swedish ultrarunner Kristina Palten ran across Iran to confront her misconceptions of Iranian culture. From the Turkish border to the Caspian Sea, Palten discovered people who were “overwhelmingly” generous and hospitable. As Brandon Stanton, the founder of Humans of New York, remarked on his trip to Iran,

“Americans are especially loved. This was noted in every travel account that I read, and I can confirm the fact. You will be smiled at, waved at, invited to meals, and asked to deliver personal messages to Jennifer Lopez. American music, movies, and media are thoroughly consumed by the people of Iran. Like all countries, there are many different viewpoints, but the vast majority of people will associate you with a culture they admire and respect.”

The reduction of Iran and its people to stereotypes of terrorists with nuclear weapons is not only inaccurate, but tragic for the cultural exchange it prevents. If the descriptions and comparisons of a nation “come more from ‘Aladdin’ than a serious understanding of that nation’s politics and culture,” says Kia Makarechi, news editor at Vanity Fair, “you should probably hand the assignment to someone else.” As Stanton suggests, travel is the “single greatest contributor to understanding between cultures.”

It is obviously impossible to make an all-encompassing conclusion for a diverse country of approximately 80 million people. Some Iranians are, in fact, firmly opposed to interacting with the United States or other Western nations. “We must burn the U.S. flag, as long as they are hostile to us,” argues one conservative analyst. The U.S. is still the “Great Satan,” Khamenei argues, no matter who the president is. But with 60 percent of Iran’s population below the age of 30, and closer to 70 percent of the population born after the 1979 revolution, the country’s younger generations are not burdened by the history that led to aggressive anti-American sentiment in the first place. In the aftermath of 9/11, candlelit vigils appeared throughout Iran in an expression of support that was unique amongst Muslim countries. “Death to America? I don’t care,” one young professional recently said, applying for an American visa. Indeed, even as the anniversary of the Iranian Revolution coincided with Trump’s travel ban announcements and thousands of Iranians gathered to burn American flags this February-- others attempted an alternative approach. With the hashtag #LoveBeyondFlags, Iranians proclaimed their support for American allies on social media. “We thank Americans who stood up for the seven countries blocked from entering the US by the new travel ban,” one Twitter account stated with the hashtag.